By Justin Jin

March 2008 — Spring arrives in Siberia as life stirs beneath the snow that has smothered it for half a year. The four of us set off for Baikal, the world’s deepest lake, near Russia’s border with Mongolia. We enter the small town Goryachinsk on the east bank after an overnight flight from Moscow and a 12-hour jeep ride. The moon is almost full, illuminating the frozen streets empty except for a few men clutching bottles of vodka around a food store. We check into our guest house with our guide, sit around a bed drilling screws into our soles to increase traction and stack luggage on our sledges.

For several months each year Baikal – the world’s largest body of fresh water, more voluminous than all the North American Great Lakes combined – freezes so solidly that locals drive their cars and lorries over it to reach towns that are only accessible by boats in summer.

For several months each year Baikal – the world’s largest body of fresh water, more voluminous than all the North American Great Lakes combined – freezes so solidly that locals drive their cars and lorries over it to reach towns that are only accessible by boats in summer.

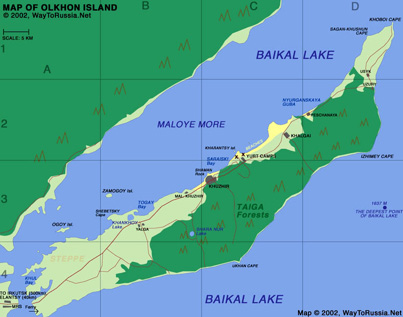

We too wanted to cross the lake, but on foot. My wife Heleen, three months pregnant with our first child, came up with the idea to trek across the crescent-shaped lake after seeing it on our map at home in Moscow. We invited our Russian friends Misha and Nastya, all of us in our mid-30s, and together we plotted a 80-km path that would give us a stop on the fabled Olkhon Island. We waited until March because February would be too cold at below -30C; but later in the season would be too dangerous as rising temperatures have already opened a web of cracks underfoot that regularly kill those who fall through.

DAY 1

It took time to find our way from the forest to the bank, but when we arrive, we are awed by

Before we set off from Moscow, where Heleen and I work as foreign journalists (she’s Dutch and I’m British-Chinese), we found an expedition company that promised to provide us with a guide and winter equipment. When we met Arkady, he seemed too disheveled and disorganized to help us avoid the cracks in the ice. As we make our first steps onto the barren ocean of ice that stretch 31,500 square kilometers, dragging our tent, clothes and provisions, our sledges keep capsizing. Nastya, who prefers shopping malls to wilderness, already hates it.

The two-metre ice is but a thin, brittle crust laying above an ancient rift valley that feels a tremor every few months (in August 2008 it was jolted by a huge 6.3 earthquake). If the water moves underneath us, we would be in trouble. Moreover, the ice is constantly under thermal strain. As the temperature falls, it expands rapidly, creating pressure ridges. When the opposite happens, ice plates contract and rip open wide crevasses that can pull cars and lorries into the abyss.

As we walk further into the lake the ice smoothes, and we use our trekking poles to gain speed and increase our metabolism. Whenever the girls lag behind in chatter, Misha would stand impatiently in the Siberian cold.

“Stop talking!” Misha shouts, while puffing another cigarette. Heleen makes him promise not to throw his cigarette buds on the lake, so he refrains from doing so when she is around.

At 5 pm, night falls suddenly, giving us little warning. The cloud that had at noon been a white fluffy blanket turns indigo, and darkness closes in on us.

Inexperienced and stupid we are, none of us, including the guide, had checked the gear before we set off. Instead of winter equipment, the company provides us with a flimsy summer tent and a few tatty foam rags as mattresses. We each try to erect the shelter in a different way, tangling the stalks and turning the tent into a mass of nylon that flaps wildly in the wind. The temperature plunges to around -15C, and the gale whips through the seams of our storm-proof clothing. All around, as far as our eyes can see, is a daunting desert of ice and snow. Our confidence collapses.

Heleen yells at everyone to stop and calmly assembles the shelter herself. We anchor it with metal ice screws, which freeze our fingers as we gnaw them into the ice. All of us dive in to the tent and I hastily cook a meal. We sleep huddled in a row, with Misha and I sandwiching Heleen and Nastya.

DAY 2

We wake as sunlight pierces the tent, unlocking our frigid bodies. This is one of the sunniest parts of Russia. We stumble on to the ice, stretch our aching limbs, pack and start to walk. The temperature rises sharply, causing ice plates to tear open gaps that streak for kilometers. Loud snapping noise darts around us.

From a distance, we see black specks that vanish and appear again. Arkady tells us they are nerpa, one of the world’s two subspecies of fresh-water seals, related to the more common Arctic seals. How they became indigenous to Baikal is still a mystery, but some scientists believe their ancestors were swept south during the Ice Age by advancing polar ice.

Soon we arrive at the spot above the deepest point of Baikal, where the lake bed plummets 1,637 metres below. As I gaze through the transparent ice into the void, I feel vertigo. We make lunch on a pressure ridge where ice plates collided. Arkady takes an axe to collect ice, which we boil to make tea. I use the ice plates as chopping board. We are in no hurry as our destination, the venerable Olkhon Island, seems within reach. Misha confirms this with the GPS and says we are one hour away. Lured by the baking sun and a full stomach, we lay like lizards atop ice formations.

Mid-afternoon and we continue to strive towards Olkhon. But, as the sun disappears behind the mountain, leaving a pink glow along the horizon, the illusive island didn’t seem any closer. Misha takes another reading from the GPS, looks to the island and drops his head again, sucks his cigarette and tells us he made a mistake: we are 25 km away, not five, as he thought.

Heleen and I dance inside when we realise this will extend our adventure. Nastya, however, is fed up with the cold and tiredness, and panics at the thought of another killer night laying on ice. Her spirits lift when the full moon and millions of stars come forward to light our journey, their shine glittering on a magical landscape of ice and snow. It is relatively warm, at -5C, and the air is perfectly still. We march on through the evening until we come, at midnight, to the edge of Olkhon Island’s majestic cliff. From lake-level, it looks fiercely rugged and immense. The 75-km-long island, accessible only by boats in the summer, is considered by shamans to be one of the five global energy poles. We hitch our tent on the ice under the cliff and marvel at the surrounding icescape, drinking Misha’s vodka.

DAY 3 – 5

Baikal is under a hot sun by the time we get up from a deep slumber. There is no way we can climb the cliff above us (we tried), so we walk another five kilometers on the ice along the shore until the mountain slopes down to Uzury, a scientific outpost that seems at once archaic and modern. We arrange for a truck to carry us to the volcanic island’s biggest human settlement, the ramshackle Khuzhir town. For an hour we drive up the mountain, through the steppe and swoop down on the western plain onto the lake again, this time on the Maloye More (Little Sea). The drive on ice is luxuriously fast and smooth compared with the bumpy roads.

Khuzhir is banked steep above the lake, overseeing the Maloye Morye and the snow-capped peaks on the mainland. Here, cattle graze the barren soil, dogs run up the windswept streets barking, and boats are locked by the ice, asleep. Trees, especially those near the Shaman rock that juts out of the coast, drip with colourful prayer rags, coins and rouble notes. We leave our guide Arkady and entered a home-stay. For the next two days we roam the island on mountain bikes, skate on the lake and enjoy banya – the traditional Russian log fire sauna.

Khuzhir is banked steep above the lake, overseeing the Maloye Morye and the snow-capped peaks on the mainland. Here, cattle graze the barren soil, dogs run up the windswept streets barking, and boats are locked by the ice, asleep. Trees, especially those near the Shaman rock that juts out of the coast, drip with colourful prayer rags, coins and rouble notes. We leave our guide Arkady and entered a home-stay. For the next two days we roam the island on mountain bikes, skate on the lake and enjoy banya – the traditional Russian log fire sauna.

Olkhon, the fourth largest lake-bound island on earth, with a population of only 1,500, is desolate, wild and breathtakingly beautiful. During our bike trip, we come upon the tiny Yalga village that seems deserted, with the post office and food store bolted. Like so many across Russia, this village is probably dying from vodka and unemployment.

There is, however, one house with smoke puffing from the chimney and clothes hanging in the garden. Heleen is cold and nauseated, so we enter the wooden gate and knock on the door. A Buryati woman in her mid-40s, Ludmilla, receives us inside her house, where we also meet her 18-year-old son, Sasha. She immediately fetches from her garden a few pieces of “Omul”, a small colourful fish found only in Baikal, that she had wrapped in newspaper and kept frozen outdoors. She cuts the raw fish into chunks. Still thawing and crunchy, it tastes like salty sorbet.

Life is tough here, says the former teacher who moved from Ulan Ude city to be with her mother, who has since died. Electricity only came to her village three years ago, and, while she can see the magnificent Baikal from her window, she has no means to collect the water and has to pay for its delivery by truck. For several months a year, when the ice is not sufficiently solid to carry vehicles but enough to hinder boats, island life is cut off from the rest of Russia.

After spending an hour with Ludmilla, we offer a bag of chocolates to Sasha and continue our journey. A large dog that looks like a German Shepard follows us to the lake and spends the next days with us.

DAY 6

Early in the morning, Nastya and Misha take a bus back to Irkutsk, while Heleen and I continue our journey from Olkhon to the western bank of Baikal, crossing the 20 km Maloye More on foot without our guide.

The sun is at full blast and the sky cobalt blue. We follow a car track on the ice, reassured that, if it can carry a heavy vehicle, it could support us. But rising temperatures are pulling ice plates apart. As we walk on, the sound of cracking thunders like a monster waiting to be sated. Suddenly, the car track vanishes into a puddle, and an empty plastic bottle bobs on the glassy open water.

Panic grips us and we dart back, seeking solid ice. We imagine the car and its passengers lodged some where below us at the bottom of the lake. The open water is just the beginning of a long crack that block our journey, so we walk along the split until it narrows, and leap across it with a rope attached to each other.

Later, we come across fishermen sitting like stones next to their cars trying to catch Omul through the ice. They are motionless except when they haul a fish or take a swig of vodka. We inform them of our morbid experience; and they tell us something about fishing, drinking and driving: in this weekend alone, 15 cars have plunged into the bottom. Except for one person who went all the way to the bottom, everyone was saved.

Heleen removes the empty vodka bottles strewn across the ice as we go along. By the time we reach land during sunset, our sledges bulge with sacks of them. This night, as we check into a small town hotel, we unload our garbage to the consternation of the hotel receptionist, who seems to wonder if we foreigners have become too fond of the Russian drink.

Back